Ultrasound to assess gastric content

Tips & Tricks: in progress

Indications: To assess the risk of aspiration of gastric content in critically ill patients

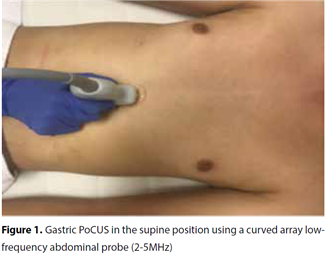

Image acquisition: The exam is best performed using a low frequency (2-5 MHz) curvillinear probe and the machine in abdominal setting. Use the sagittal plane between the xiphoid and the umbilicus, with the patient lying in the supine and right lateral decubitus position (Figure 1: adapted from Soe-Loek-Mooi et al Neth J Crit Care 2019; 27 (1): 6-13).

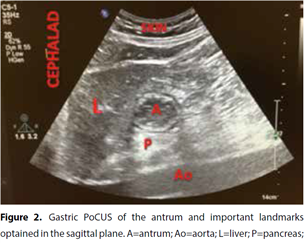

Normally, the left side of the liver provides a good acoustic window for visualizing the gastric antrum, which is the most accessible part of the stomach due to its superficial location in epigastrium. This is in contrast to the gastric body and deeper located gastric fundus. The probe is gently swiped from the left to the right subcostal margins and gently tilted and rotated to make the antrum appear as a hollow viscus identified by several important landmarks: 1. the left lobe of the liver; 2. body of the pancreas; 3. abdominal aorta; 4. inferior vena cava; and 5. both the superior mesenteric artery and vein (Figure 2). Make sure you have the liver, aorta or inferior vena cava and antrum in the same ultrasound image in a sagittal section. In this way you know that you image the antrum of the stomach. The antrum is first scanned in supine and then right lateral decubitus position. This increases the accuracy to assess gastric content in low(er) volume states. Of note, the antrum reflects the contents of the entire stomach. When an examination is limited to the supine position, it can grossly underestimate the amount of gastric content and therefore the aspiration risk. In patients in whom the examination in right lateral decubitus position is not feasible, e.g. traumatic brain injured patients, a semi-recumbent position (with the head elevated in 45 degrees) may be an acceptable alternative.

The gastric wall appears 4-6 mm thick and consists of five distinctive layers (from inner to outer surface): 1. hyperechoic mucosal-air interface; 2. hypoechoic muscular mucosae; 3. hyperechoic submucosa; 4. hypoechoic muscularis propria; and 5. hyperechoic series-surrounding tissue interface. These layers help differentiate the stomach from other hollow organs.

Image interpretation:

Qualitative assessment of gastric content: empty, clear fluid or thick fluid/solid contents?

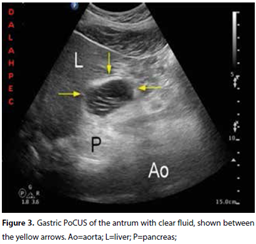

Determining the quality of the gastric content is a major aspect in predicting aspiration risk. When the stomach is empty, the antrum appears small and may be either round or ovoid resembling a bull`s eye target pattern due to the absence of content, or flat with the anterior and posterior walls of the antrum juxtaposed. If clear fluid is present, the antrum increases in volume, becomes round and distended, with hypoechoic/anechoic content (Figure 3). Gastric secretions, water, apple juice, tea and coffee appear hypoechoic or anechoic. Thick fluids or suspensions have increased echogenicity. The mixture of air bubbles or gas suspended in a background of clear fluid gives the antrum the aspect of a ‘starry night.’ These gas bubbles disappear rapidly within minutes of ingestion. After a solid meal, the air mixes with the solid food during the chewing and swallowing processes. The amount of air, solids and liquid ingested in a larger meal will give the appearance of heterogeneous content with large particles or a ‘frosted-glass’ pattern on ultrasound imaging.

Quantitative assessment of gastric content volume

To assess gastric content volume, first the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the antrum is measured by one of the following methods:

1)The two-diameter method, which calculates the CSA by measuring two perpendicular diameters of the antrum from serosa to serosa, assuming that the antrum has an elliptical shape and using a standard formula of the surface area of an ellipse.

Formula: CSA= (AP ×CC × π)/4

where AP represents the anteroposterior antral diameter, CC represents the craniocaudal antral diameter.

2) The free-tracing method, which is applied by using the free-tracing calliper of the ultrasound machine to measure the antral CSA. It is a simpler method that relies on a single dimensional measurement and does not require a formula. It has been shown to be accurate and to provide similar results to the two-diameter method.

Essentially, both methods are equal, e.g. for a volume of 300 ml in the stomach, the difference between the two methods is not greater than 25 ml.

Limitations:

Gastric PoCUS offers many advantages and can potentially prevent devastating complications, however, it has some limitations. As for every PoCUS exam, there is the chance of variability between observers. Also, modest tilting of the probe is sometimes necessary for optimal imaging but can result in oblique images of the antrum causing an overestimation of the antral CSA and thereby gastric fluid volume. This can create a false image of an at-risk stomach. However, closely following a standardised scanning technique as previously described and a rigorous method of measurement can minimise inter-observer variability and increase accuracy and reliability.

While most studies used a gastric fluid volume of 100 ml or >1.5 ml/ kg in adults as indicative of an ‘at-risk’ stomach, this threshold remains controversial and is a matter of debate.

Lastly, all studies have excluded patients with pre-existing abnormal anatomy of the upper gastrointestinal tract, e.g. previous oesophageal or gastric surgery, or hiatus hernia, meaning that there are no data on predicting aspiration risk for these groups of patients when using gastric PoCUS.

References:

Ultrasound to assess gastric content and fluid volume: new kid on the block for aspiration risk assessment in critically ill patients? S.A. Soe-Loek-Mooi, N.S. Tjahjadi, A. Perlas, P. van de Putte, P.R. Tuinman. Neth J Crit Care January 2019;27(1): 6 - 13

Chief-editors

Pieter Roel Tuinman, MD, PhD, intensivist-epidemiologist

David van Westerloo, MD, PhD, intensivist

Editors:

Carlos Elzo Kraemer, MD, intensivist

Jorge Lopez Matta, MD, intensivist

Paul Wijnandts, MD, intensivist

Jasper Smit, MD, PhD student

Mark Haaksma, MD, PhD student

Micah Heldeweg, MD, PhD student

Annemijn Jonkman, technical physician, PhD student

Heder de Vries, MD, PhD student

Contact

Department of Intensive Care Medicine

Amsterdam University Medical Centres, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

Room ZH - 7D-166

De Boelelaan 1117

1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

prtuinman@hotmail.com

Department of Intensive Care Medicine

Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC)